Some thirty features of AIDS in Africa

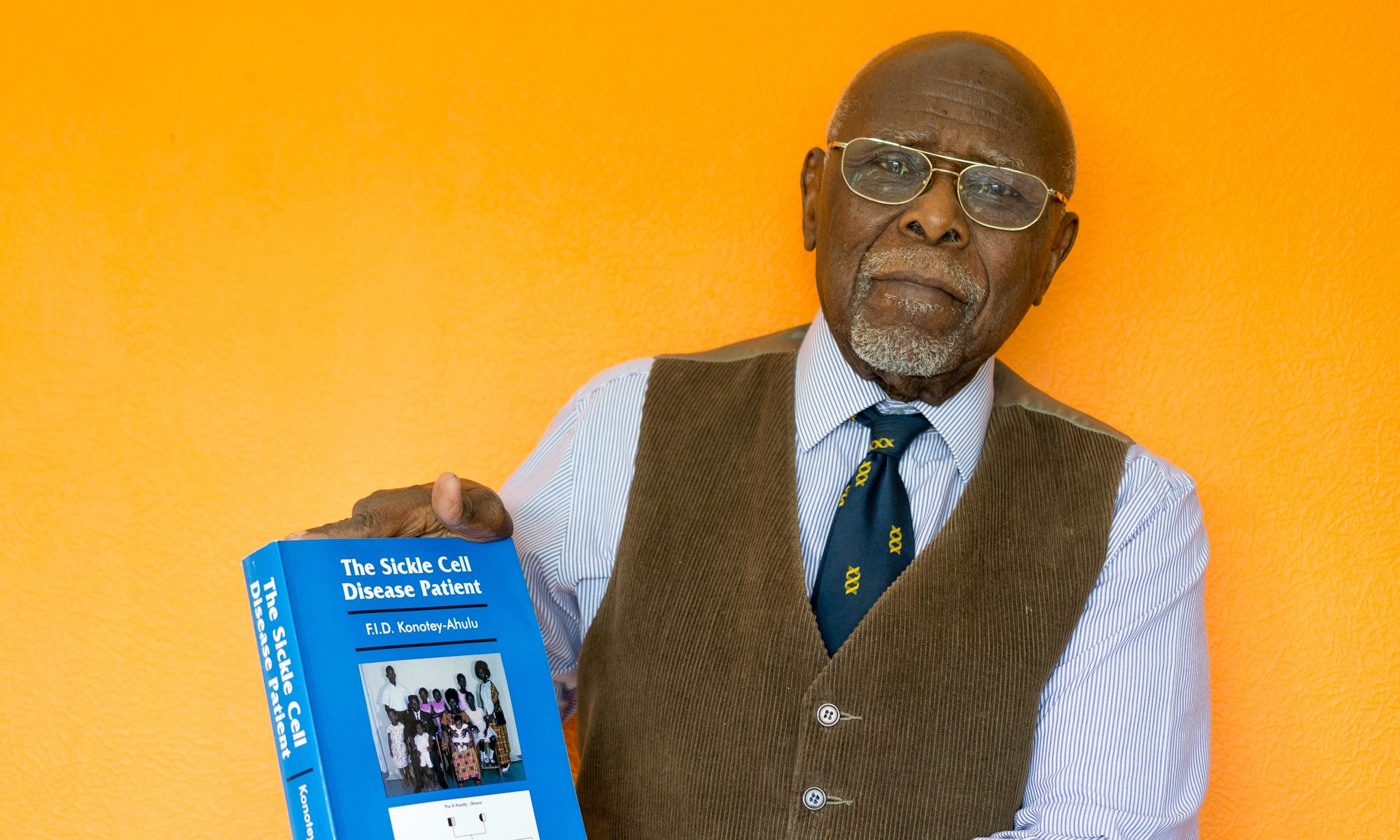

KONOTEY-AHULU F.I.D.*

In 1987 I visited sixteen African countries to acquaint myself with the AIDS situation on the continent. I obtained information from doctors and health workers about many of the countries I could not visit. 1 was refused a visa to go to

A synoptic overview of clinical and other features of AIDS in

Aids is not uniform over the 50 countries in

Age block gap. No patients were found between infancy and teens except the blood trans-fused, thus excluding insect vectors in transmission (Dr. Miriam Duggan and Dr. Sewankambo of

Repatriation AIDS. In my Krobo tribe in

100 % Female preponderance. In certain tribes in

Perineal devastation easily visible from the foot of the bed with undressed patient lying prone (Dr. Mate-Kole, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital,

Virgins and the nulliparous can get AIDS from the first intercourse due to tears (Dr. Mate-Kole, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital,

Pervisemos i.e. ‘persistent virus secreting mothers’ who are asymptomatic but continue to bring forth sick children (Dr. Duggan and Dr. Hanny Friesen, Kampala ; Dr. Chintu, Lusaka).

AIDS Precipitators. Caesarian section and minor procedures like salpingohistograms can turn the asymptomatic into full blown AIDS (Dr. Duggan,

Former Director Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics, and Consultant Physician, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital,

*Published in: Annales Universitaires des Sciences de la Santé 1987; 4 (4): 541-544.

Symptomatology of Slim : 20-40 % weight loss, persistent diarrhoea, fever, lymphadenopathy, respiratory symptoms, oral candidiasis and amenorrhoea in child bearing women, with frequent previous history of sexual exposure, of blood transfusion, and/or unsupervised injections (Dr. Sezi, Serwadda & colleagues in Kampala, physicians in Dar es Salaam, and in Lusaka and Ndola, Zambia, Dr. Neequaye et al, Ghana) (6, 7, 8).

Intractable Pruritus in adults, and in infants : this could be the commonest cause of

insomnia (Dr. Chintu and Dr Subhash Hira,

Generalised hyperpigmentation with crazy-pavement dermatopathy (Professor. Bodo,

Dupuytren's Contracture (Professors Badoe, Archampong and Jaja's new book

“Surgery in the Tropics” p.210 shows this physical sign as a complication of plaque Kaposi's sarcoma) (9). Professor Anne Bayley (Lusaka

Elephantiasis of limbs (upper and/or lower) and genitals from AAKS (Professors

Multidermatomal Herpes Zoster heralds full blown AIDS (Dr. Subhash Hira,

Adult Kwashiorkor. I saw this syndrome in my Krobo tribe where girls with Repatriation AIDS whose diarrhoea must have included creatorhoea with consequent protein calorie malnutrition.

Accelerated orphan Kwashiorkor. 1 saw this at

Tuberculous pericarditis as a common complication (Dr. Mboussa,

Non-AIDS Diseases producing HIVseropositivity. (Dr. Fleming and Rosemary Mwendapole, Ndola , Zambia

Anti-TB treatment to fake seropositivity.

Radiological “bat's wing” lung in AAKS (Professors Bugingo

Sworl Facies: a characteristic “Strikingly worried look”, on the faces of the more discerning patients I visited on ward rounds in

Relative Paucity of full blown AIDS. It came as a surprise to find a Zairean man and wife, and a Kenyan itinerant salesman as the only AIDS patients in the 2100-bed

Patients are not dying “like flies” as world media report (13). When

Seropositive twin baby lives while seronegative twin dies. Born to a pervisemo (ie persistent virus secreting mother) the infected twin lived while the seronegative twin died from AIDS, in

AIDS has not changed health priorities in Africa. I cannot speak for

Disagreement about seriousness of the problem. Some expatriate workers in

prophesy doom, but most indigenous doctors while not underestimating the gravity in some countries, consider forecasts exaggerated (

Grade I, not much of a problem; Grade II, a problem exists; Grade III, a great problem;

Grade IV, an extremely great problem, and Grade V, a catastrophe (13). I recommend this approach to health workers and urge them to have their own grading criteria. Clinicoepidemiology rather than seroepidemiology will best bring out the truth about the real state of affairs of each country (1).

The Juliana Phenomenon. AIDS in the lake region of Tanzania, bordering Zaire, is known as “Juliana” because, as one prostitute told me, “A few years ago when the Navy visited Mombasa with 9, 000 troops, some of our girls who travelled there for business were given T shirts with Juliana marked on them. Many of those who wore the Juliana shirts have since had Slim and died”.

Non-Africans with AIDS. The 6 patients seen in Mombasa with AIDS (1983-1987) by a specialist, were a Zairean, and 5 non-Africans from Europe and the USA; in South Africa all the AIDS has so far occured in non-blacks (Dec 1987), and in Zaire at least 21 Europeans and Americans were known to have had AIDS (Source : Resident Greek Businessman). HIV-2 in

Complete Cure Anecdotes were heard in

Comment

It is important that doctors living and working in

And she replied, “Oui Monsieur, mais je leur demande une grande somme d'argent”

(17). So, one should now use “peno-vaginal sex” for so called heterosexual sex, and “anal sex”or “sodomy” for what is called “homosexual relationship”. Anal sex has been demanded sometimes for money in several countries in

Finally the kind of research that will help Africans curtail AIDS does not have to be the vaccine orientated research of the developed countries. Public Health methods and clinical epidemiology are

Acknowledgements

I thank the clinicians who took me on ward rounds during my recent

REFERENCES

1. KONOTEY-AHULU F I D, (1987) Clinical epidemiology, not seroepidemiology, is the answer to

2. NEEQUAYE A.R., NEEQUAYE J,., MINGLE J.A., OFORI-ADJEl D. (1986). Propondernace of females with AIDS in

3. NEEQUAYE A. R., ANKRA-BADU G.A., AFRAM R.A. (1987). Clinical features of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in

4. KONOTEY-AHULU FID (1987) AIDS: origin, transmission and moral dilemmas. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 80: 720.

5 KONOTEY-AHULU FID (1987). Surgery and risk of AIDS in HIV positive patients. Lancet ii: 1146

6. SERWADDA D., MUGERWA R.D., SEWANKAMBO N.K, LWEGABA A.,

CARSWELL J. W, KIRYA G.B., BAYLEY A.C., DOWNING R.G., TEDDER R.S., CLAYDEN

7. SEWANKAMBO N., MUGERWA R.D., GOODGANER R.,CARSWELL JW, MOODY A., LLOYD G., LUCAS S.(1987). Enteropathic AIDS in

An endoscopic, histological and microbiological study. AIDS 1:9

8. SEWANKAMBO N., CARSWELL J. W,. MUGERWA R.D., LLOYD G., KATAAHA P.,

DOWNING R.G., LUCAS S.(1987) HIV Infection through normal heterosexual contact in

9. BADOE E.A., ARCHAMPONG E.Q., JAJA M., Eds, Principles and Practice of Surgery in the Tropics.

10. FLEMING A.F., KAZI A.R., SCHEINEDER J., GUILLOT F., MWENDAPOLE R., WENDLER I., HUNTSMANN G. (1986). Comparison of HTLV-111 in some Zambian patients. AIDS Forschung (AIFO) 8: 434.

11. BAYLEY C A. (1983). Aggressive Kaposi’s sarcoma in

12. MONEKOSO G. In Second International Conference on AIDS in

13.KONOTEY-AHULU F I D. (1987). AIDS in

14. BRUCKER G, BRUN-VEZINET F,

15. KINGMAN SHARON. (1987). The Portuguese connection. New Scientist, 15th October, p 27

16. QUARTEY J K M, MATE-KOLE M O, OKAI GLORIA, BENTSI CECILIA, DJABANOR F F T, KONOTEY-AHULU F I D. (1988). Domicilliary management and prognosis of AIDS in the Krobo region of South east

17. KONOTEY-AHULU F I D. Extensive palatal echymosis from felllatio – a note of caution with AIDS at large. (1987). British Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14: 286-287

18. PALLANGYO K J, MBAGA I M, MUGUSI F, MBENA E, MHALU F S, BREDBERG U, BIBERFIELD G. (1987). Clinical case definition of AIDS in African adults. Lancet, ii: 972.

First published in Annales Universitaires des Sciences de la Santé 1987; 4: 541-544

Postscript January 2008: What has happened in

References

(i) Guisselquist D, Rothenberg R, Potterat J, Drucker E. HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa not explained by sexual or vertical transmission. Internatrional Journal of HIV & AIDS Oct 2002: Vol 13: pages 657-666.

(ii) Fassin D, Schneider H. The politics of AIDS in

(iii) Financial Times. AIDS in

(iv) Konotey-Ahulu FID. AIDS in